Click here to listen to our newest addition: Boardrooms’ Best Podcast.

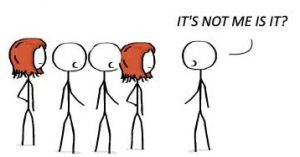

The new year, and setting resolutions, such as improving oneself, arrive together. For me this includes taking stock of all the top of mind individuals in my life and business. Relationships with those who have helped me along, have been good friends and allies, and the ones who have my trust, I nurture and support. Those who have been especially irksome, even toxic, I move aside. This process can be difficult, and takes more courage than one might think. However, cutting through tough emotional attachments and letting go, if done right, can be quite cleansing. It also opens new pathways to higher rewards and returns. If you’ve never done this before, give it a try. You may feel as though a ton of bricks has been lifted off your shoulders.

The new year, and setting resolutions, such as improving oneself, arrive together. For me this includes taking stock of all the top of mind individuals in my life and business. Relationships with those who have helped me along, have been good friends and allies, and the ones who have my trust, I nurture and support. Those who have been especially irksome, even toxic, I move aside. This process can be difficult, and takes more courage than one might think. However, cutting through tough emotional attachments and letting go, if done right, can be quite cleansing. It also opens new pathways to higher rewards and returns. If you’ve never done this before, give it a try. You may feel as though a ton of bricks has been lifted off your shoulders.

The same holds true for boards. Directors who lack relevance, show blatant conflicts of interest, seem tuned out, fall asleep or text during meetings, test the patience of their colleagues (rare, but almost all directors like to vent about them), drag down the rest of the board. While these directors may seem to be only annoying, in reality they can be quite harmful to a board. In some cases, it’s not the deliberate intent of the directors: the business, industry, and/or company may have just evolved beyond their capabilities. Time marches on, edges dull, interests fade. An INSEAD study reported that the professionals serving in the same roles tend to have performance declines after about eight years.

That said, when the time comes, how do you cut the cords? It’s not like a board can just stop calling or taking calls from a director and hope (s)he just goes away. To do this well, you need to have a process already in place, one that finds and deals with the facts, preserves respect, avoids the emotional aspects, and gets the job done right. Here are some thoughts:

Get your facts straight.

Get your facts straight.

But who will do it? If a chairman or lead director is uncomfortable in having these types of discussions, an independent advisor, or the Chief Human Resource Officer (CHRO), or General Counsel and Corporate Secretary (GC/CS), if they have the correct EQ, can support the process. Kevin Silva, Chief Human Resource Officer (CHRO) at the insurance giant VOYA Financial Services, who’s worked with boards through all phases of governance life cycles, shares that “removing a director is the last step in a failed process. ” In many cases, a well-seasoned CHRO can help guide the board through the ‘parting’ process.

However, if one can draw on the expertise of management or outsiders for support, counsel, and guidance in conducting the conversation, it’s probably best not to involve them directly in “pulling the trigger.” Independent directors need to be viewed as independent, in all phases of their service. So, even when it’s time to go, this is best dealt with independent director to independent director. But, the most levelheaded, respected member should be the one to handle the conversation.

It’s important to note,: as Harvey Pitt former Chair of the SEC stated: “removal of a director must still be done in an organized way and in a manner to persuade a whole set of constituencies that it was fair, legal, logical, and in the best interest of the shareholders.”

![]() Do the next steps, too.

Do the next steps, too.

If the situation arose from bringing on the ‘wrong’ person, it may be time to scrutinize the board’s recruiting and vetting processes. Another important set of questions should center around what we’re not seeing. Do others – analysts, activists, institutional investors, and the like, have different perspectives on the quality and appropriateness of those sitting beside us at the table? Maybe it’s time to give their viewpoints another look. After all, there is no one board member who can succeed on every single board out there.

So you see, breaking up is often hard to do. But someone always has to do it. Kinda like board work.